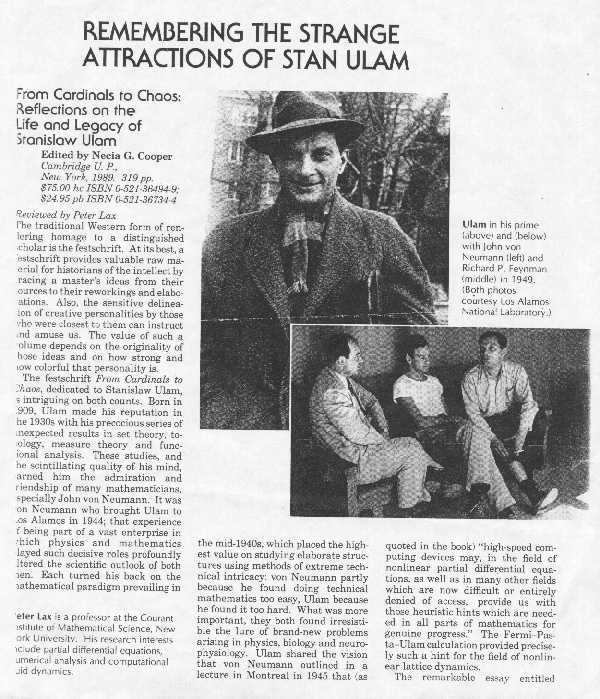

About Stanislaw UlamAt the beginning of his Adventures of a Mathematician (2d ed., Berkeley, 1991), Stan Ulam retrieves a very early memory: "When I was four, I remember jumping around on an oriental rug looking down at its intricate patterns. I remember my father's towering figure standing beside me, and I noticed that he smiled. I felt, 'He smiles because he thinks I am childish, but I know these are curious patterns.' I did not think in those very words, but I am pretty certain that it was not a thought that came to me later. I definitely felt, 'I know something my father does not know. Perhaps I know better than my father.'" This fascination carried him through a long life that reached across continents, oceans and universities; and that spanned the end of the last European empire, two world wars, and the age of nuclear weapons, which his genius helped make possible.In its notes accompanying its catalog of the archive of his papers, the American Philosophical Society summed up his achievements: "Stanislaw Ulam was a gifted mathematician who, during the course of his career, made significant contributions to set theory, topology, ergodic theory, probability, cellular automata theory, the study of nonlinear processes, the function of real variables, mathematical logic, and number theory. Perhaps his greatest achievement was the deveopment of the Monte Carlo method for solving complex mathematical problems by electronic random sampling, but he made equally noteworthy contributions in hydrodynamics (three-dimensionnal fluid flow), the development of nuclear propulsion for space flight (Project Orion), and in fields as disparate as physics, biology and astronomy. Yet despite the breadth of his scholarship, Ulam is most often remembered for the central role he played in the early development of the American hydrogen bomb." Necia G. Cooper, ed., From Cardinals to Chaos: Reflections on the Life and Legacy of Stanislaw Ulam (New York, 1989) is a collection of commemorative essays by colleagues. In his review in Physics Today (June, 1989), NYU Mathematics Professor Peter Lax noted: "The remarkable essay entitled 'The Lost Café,' written by Gian-Carlo Rota, serves as the introduction to this volume. Rota knew Ulam for the last 21 of his 75 years -- the same span for which James Boswell knew Samuel Johnson. The essay is a kaleidoscopic picture, filtered through Rota's eyes and ears, of Ulam's life and thoughts, his psychological makeup, the influence on him of his Eastern European background and of the destruction of Europe during the Second World War, his friendship with von Neumann and the thrill of being part of the great scientific enterprise at Los Alamos."  Stanislaw Ulam, who died in 1984, remains a noted mathematician. Here he is [r.], in 1935 at age 26, on a street in Lwów with colleague Stefan Mazur, perhaps headed for one of the cafés where the Lwów mathematicians gathered. Their favorite was the "Café Szkocka" (the Scottish Café). But only a few years later, as he would recall in Adventures. . .,

Stanislaw Ulam, who died in 1984, remains a noted mathematician. Here he is [r.], in 1935 at age 26, on a street in Lwów with colleague Stefan Mazur, perhaps headed for one of the cafés where the Lwów mathematicians gathered. Their favorite was the "Café Szkocka" (the Scottish Café). But only a few years later, as he would recall in Adventures. . ., " . . .These were the last days of August [1939]. . .Adam and I were staying in a hotel on Columbus Circle. It was a very hot and humid New York night. I could not sleep very well. It must have been around 1:00 in the morning when the telephhone rang. Dazed and perspiring, very uncomfortable, I picked up the receiver, and the somber throaty voice of my friend , the topologist Witold Hurewicz, began to recite the horrible tale of the start of the war: 'Warsaw has been bombed, the war has begun," he said. He kept describing what he had heard on the radio. Adam was asleep; I did not wake him. There would be time enough to tell him the news in the morning. Our father and sister were in Poland, so were many other relatives. At that moment, I suddenly felt as if a curtain had fallen on my past life, cutting it off from my future. There has been a different color and meaning to it ever since. . . ."

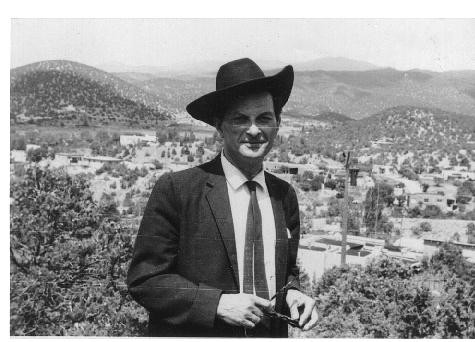

Much later . . . two pictures from the 1960's. In the one on the right, the background contains land that he bought outside Santa Fe, NM in 1947. In 2002, the Hudson Valley Writers' Center, under the imprint of Slapering Hol Press, published The Scottish Café, a book of poems by Susan H. Case, who teaches sociology at the New York Institute of Technology. She notes: "This series of poems is loosely based upon the experiences of the mathematicians of the Scottish Café, who lived and worked in Lwów, Poland (now L'viv, Ukraine), a center of European intellectual life before World War II. . . . A book, known as the Scottish Book, was kept in the Café and used to write down some of their problems and solutions. Whoever offered a proof was often awarded a prize." FUSION

there was too much of Lwów, and now there isn't any . . . . --Adam Zagajewski Ulam in America is homesick Colorado doesn't have winters as marvellously brutal as Lwów he misses arguing with the other mathematicians over whether the Scottish or Roma café has better bread besides ever since he taught in LA there is a glitch in the wiring of his brain a change not only in weather but personality I do the big ideas now he tells his students the details are for others but he can't help shouting his jokes stories limericks mixed with the grand ideas compression from shock waves from fission essential to explosion nuclear propulsion his friends think he behaves a little oddly but no one is allowed to talk about it or the dilemma of having to carry everything including his lemmas and formulas in his head not writing them down his mind too fast for his hands maybe it's an eye problem his wife pleads for him to get glasses eventually he does but still avoids paper after all—what could be larger than Teller and the thermonuclear bomb but mostly he wears the glasses to watch snow fall as he stands wistful at the kitchen window where he likes the way the snow settles in the crooks of the aspen trees in his sleeping backyard remembering the time before the deportations the chestnut trees of Lwów by Susan H. Case in The Scottish Cafe (New York, Slapering Hol Press, 2002) Reproduced by permission. If ever there was uncertainty about which of the many brilliant intellects among the Los Alamos scientists contributed most decisively to the workability of the fusion device, uncertainty never dwelt and does not to this day dwell in the mind of Edward Teller, who died September 9, 2003, at the age of 95. In an article in the Boston Globe of December 11th entitled "Force of Physics" [© copyright 2001 by The Boston Globe Company], Mark Feeney wrote of an interview with Teller: " No one had argued as fiecely for the [fusion] bomb, worked as hard on it, or made as great a scientific contribution. The question of how great a contribution still rankles. The consensus view is that credit should go almost equally to Teller and the Polish-born mathematician Stanislaw Ulam. Teller disagrees. 'There was one who took credit because he was very good at taking credit. He certainly did not deserve it. You know who I mean. Say it,' he urges Shoolery [Judith Shoolery, co-author of Teller's memoirs]. 'Stan Ulam,' she says. "When it's pointed out that no less an authority than Herbert F. York, the founding director of Lawrence Livermore [Laboratories], has written that 51 percent of the credit belongs to Teller and 49 percent to Ulam, Teller protests. 'My view is that I deserve 101 percent of the credit, and Ulam minus-1 percent.' He means this to be funny. . . , but it's not entirely clear that he's joking." Stan Ulam himself recalled, in autobiographical notes among his papers at the American Philosophical Society [here quoted by permission of the APS], "Already, in 1945, I was asked to visit Los Alamos once or twice for conferences on the possibility of constructing the so-called 'super,' the hydrogen bomb. The problems connected with these possibilities were studied already during the war in Los Alamos, especially by Teller's group and, in general, in the division headed by Fermi. During the war, I became very friendly with Fermi and we had countless discussions on all sorts of topics in physics and about the world in general. When we came back to Los Alamos, I found still a number of friends from the wartime years there. Richtmyer, Metropolis and others with whom I had done some work previously were there. What was most stimulating is that many of the previous participants in the project returned during the summer for long stays. So, for example, von Neumann was a very frequent visitor and so was Fermi. I worked on the theory of the Monte Carlo method on problems of hydrodynamics of matter and of radiation. In 1948 and 1949 Teller came back to Los Alamos. When it was decided to proceed with the project of planning and development of the hydrogen bomb, I was engaged in intensive work on all problems connected with it. This story has been told in various places. In 1947 I persuaded my mathematical collaborator, Everett, to come to Los Alamos. (He is still there.) Together, we managed to show that the original schemata for the construction of a thermonuclear device were insufficient and, in my work with Fermi, we managed to show that the proposed ideas were inadequate. Shortly afterwards, I was thinking of some other approaches which, together with some ideas of Teller, led to the successful plan for construction of a successful thermonuclear explosion (the H-bomb)." But as recently as eleven years ago, additional facts, hitherto classified, began to surface and be the basis for informed opinion. In an article in Time of January 15, 1990 [© 1990 by Time-Life, Inc.], Philip Elmer-DeWitt referred to Soviet spy Klaus Fuchs, whose traffic included the ongoing work on the hydrogen bomb. On the actual usefulness of what Fuchs sent over, Elmer-DeWitt wrote: "Fuchs's betrayal of the H-bomb secrets passed into the folklore of of the nuclear age. The folklore, however, is false. Fuchs's H-bomb plans were totally misleading, and Truman's rationale for rushing to build the bomb before the Soviets did was on shaky ground. That is the conclusion of an article in the January-February issue of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, one of a series of scholarly works that are rewriting a period of U. S. history still shrouded in mystery and official secrecy. According to Daniel Hirsch and William Matthews, what Fuchs gave the Soviets was an early design of Teller's that turned out to be unworkable. The crucial insight, they say, came after Fuchs had been imprisoned, and it was supplied not by Teller but by his Los Alamos colleague Stanislaw Ulam. Says Hirsch, former director of the nuclear-policy program at the Univeristy of California at Santa Cruz: 'In many ways, Stan Ulam was the true father of the H-bomb.'" |